Rose Pathology in the Northeast: Start with genetics, reinforce with IPM, use fungicides wisely

Authors: John DeCarlo, PhD, and Elizabeth M. Adler, PhD

Elizabeth.adler@uconn.edu

Publication EXT153 | September 2025

Reviewer: Peter Winne of Peter Winne Gardens

Introduction

Roses are often planted as an integral part of Northeastern gardens, valued for their ornamental and cultural significance. Despite their popularity, they are prone to several fungal diseases that can reduce plant vigor, flowering, and landscape performance. The Northeast’s climate—characterized by high humidity, frequent rainfall, and prolonged leaf wetness—creates ideal conditions for disease development.

Successful rose culture in this region depends on recognizing that plant genetics, cultural care, and judicious use of fungicides serve as guardians against disease. Choosing resilient cultivars equips the plant itself to withstand infection, while cultural practices such as proper siting, pruning, irrigation, and sanitation reshape the growing environment to reduce stress and inoculum. Natural fungicides add another layer of defense by creating protective barriers, and conventional fungicides—used carefully and in rotation—reinforce these protections when pressure is high. Together, these measures form a coordinated strategy that allows roses to thrive with beauty and fragrance for decades.

This fact sheet demonstrates that the guiding theme— start with genetics, reinforce with IPM, and use fungicides wisely—is more than a slogan; it is a proven framework for success. Resistant cultivars reduce vulnerability at the outset, IPM practices continually reshape the environment to suppress pathogens, and fungicides, applied thoughtfully, provide a safety net when pressure is high. When these elements work together, the disease triangle is disrupted, the balance shifts in favor of health, and roses can flourish year after year with more disease resistance, fewer diseases, and greater resilience.

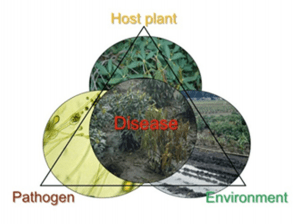

The Disease Triangle

Plant pathologists use the disease triangle to explain why plant diseases occur. Disease develops only when three conditions align: a susceptible host, a virulent pathogen, and a conducive environment. In the Northeast U.S., the environmental leg of the triangle—long periods of leaf wetness, high humidity, and frequent rainfall—often tips the balance toward infection.

Genetics and cultural practices act as capable guardians by breaking sides of the triangle before disease gains a foothold. Selecting resistant cultivars strengthens the ‘host’ side, while good cultural practices—spacing, pruning, irrigation management, and sanitation—alter the ‘environment’ so it no longer favors fungal growth.

When natural fungicides such as sulfur, copper, neem oil, or phosphites are added, they further reduce environmental favorability by creating protective barriers. In seasons of high disease pressure, conventional fungicides may be needed, and their careful rotation prevents pathogens from overcoming these defenses. Together, these strategies reshape the triangle, tipping the balance toward health and resilience.

Table 1: At a Glance, Major Fungal Diseases in the Northeast affecting Roses

| Disease | Typical Symptoms | Weather Trigger | First Action | Long-Term Strategy |

| Black Spot Diplocarpon rosae |

Lesions with feathery margins and repeated defoliation; spores germinate after ≥6 hours of leaf wetness. | Warm, rainy, ≥6 h leaf wetness | Remove leaves, apply protectant | Resistant cultivars; rotate FRAC groups |

| Powdery mildew Podosphaera pannosa |

White growth on young leaves and buds during warm days/cool nights. | Warm days, cool nights, humid | Prune congested growth | Avoid late watering; resistant cultivars |

| Downy mildew Peronospora sparsa |

Angular purple lesions, sudden defoliation in cool, wet conditions. | Cool (40–74°F), prolonged wet | Improve airflow; phosphites | Replace highly susceptible cultivar |

| Cercospora Leaf spot Cercospora rosicola |

Purple lesions with gray centers; increasingly common in hot, humid summers. | Hot, humid summers | Sanitation | Select tolerant cultivars |

| Anthracnose Sphaceloma rosarum |

Circular lesions with pale centers and “shot-hole” appearance; favored by cool, wet spring. | Cool, wet spring | Remove infected canes | Increase spacing and airflow |

| Botrytis blight Botrytis cinerea |

Gray mold on petals and buds; most severe on high-petal cultivars after rain. | Cool, wet, stagnant air | Deadhead, remove debris | Thin canopy, avoid high-petal roses in wet sites |

| Rust Phragmidium spp. |

Produces orange to yellow pustules on the undersides of leaves; sporadic in the Northeast but occasionally severe in cool, moist springs. | Cool, moist spring | Remove infected leaves | Plant resistant cultivars |

Selecting the Right Roses

Cultivar choice is the foundation of rose disease management. Programs such as Earth-Kind® have shown that roses can thrive without sprays when genetic resistance is strong. The American Rose Trials for Sustainability (ARTS®) provide additional trial-based validation, including in the Northeast. Local experience is also critical; Winne (2021) documents several roses performing reliably in Connecticut gardens.

Table 2.Disease-Resistant Roses for the Northeast (Zones 3–7a)

| Cultivar | Class | Zone | BS | PM | Notes |

| Hansa | Rugosa | 3–8 | High | High | Hardy, fragrant, produces hips. |

| Maiden’s Blush | Alba | 4–8 | High | High | Shade-tolerant, clean foliage. |

| Rosa Mundi | Gallica | 4–8 | High | High | Striped historic rose, reliable foliage. |

| Carefree Beauty✦ | Shrub (Buck) | 4–9 | High | Mod | Earth-Kind®, stalwart performer. |

| Earth Song✦ | Shrub (Buck) | 5–9 | High | Mod | Earth-Kind®, floriferous shrub. |

| Sea Foam✦ | Groundcover | 5–9 | High | High | Earth-Kind®, trailing, tolerant foliage. |

| Belinda’s Dream✦† | Shrub | 6b–9 | High | Mod | Large pink blooms; marginal in colder zones. |

| Bonica | Shrub (Meilland) | 4–9 | High | Mod | Reliable landscape performance. |

| Knock Out® | Landscape | 5–9 | High | High | Benchmark low-maintenance rose. |

| Plum Perfect | Kordes/ADR | 5–9 | High | Mod | Modern cultivar, healthy in trials. |

| South Africa★ | Floribunda (Kordes) | High | Mod | ARTS winner, golden blooms, excellent foliage. | |

| Sunshine Daydream★ | Grandiflora (Meilland) | 5–9 | High | High | ARTS winner, strong disease resistance. |

✦ = Earth-Kind® designation (Texas A&M AgriLife)

† = Hardy only in southern Northeast (Zones 6b–7a)

★ = American Rose Trials for Sustainability (ARTS®) award

Integrated Pest Management (IPM)

Cultural practices form the backbone of rose health:

- Sun and spacing

- Six or more hours of direct sunlight (preferably morning light); allow space for airflow;

- Irrigation

- Drip or soaker hoses; avoid overhead watering late in the day;

- Mulch and sanitation

- Apply two to three inches of organic mulch; remove fallen leaves and petals, they carry disease;

- Pruning

- Open the canopy, remove weak or crossing canes.

Beneficial insects such as lacewings, lady beetles, predatory mites, and parasitic wasps help indirectly by reducing insect damage that predisposes plants to infection.

Fungicides and Resistance Management

Fungicides are a support tool, not the foundation of rose disease management. They should be considered only after cultural practices and resistant cultivars are in place, and they work best when applied preventively before disease takes hold.

Low-Risk and Natural Options

The Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC) assigns codes to fungicides based on their mode of action. Several materials are considered low-risk or ‘natural’ fungicides. These can be valuable where gardeners want to minimize synthetic inputs, or as first steps in an integrated program:

- Sulfur (FRAC M02)

- effective protectant against black spot and powdery mildew; avoid use in high heat or near oil applications;

- Copper (FRAC M01)

- broad protectant; can cause leaf bronzing if over-applied;

- Bicarbonates

- disrupt fungal growth on contact; best for early suppression of powdery mildew;

- Phosphites (FRAC 33)

- stimulate plant defenses and provide protection against downy mildew during cool, wet periods;

- Neem oil and horticultural oils

- smother spores and reduce surface growth; also help suppress insects and sooty mold. Avoid applying oils within 10–14 days of sulfur and during very hot weather;

- Biologicals (e.g., Bacillus or Trichodermaformulations)

- variable results, but useful as part of an organic IPM program.

These products generally require more frequent reapplication (7–10 days, or after heavy rain), and thorough coverage of both leaf surfaces. They are best viewed as first-line tools in low to moderate disease pressure.

Conventional Fungicides and FRAC Rotation

Where disease pressure is high, or cultivars are more susceptible, systemic or single-site fungicides may be necessary.

- Contact protectants (multi-site): sulfur, copper, mancozeb.

- Systemics/penetrants:

- DMIs (FRAC 3) – myclobutanil, tebuconazole.

- QoIs (FRAC 11) – azoxystrobin.

- SDHIs (FRAC 7) – mostly commercial; active against foliar pathogens.

To avoid resistance, products in the same FRAC group should not be used consecutively. The most effective strategy is to alternate between multi-site protectants and single-site products, adding a weather-triggered addition of phosphites (FRAC 33) when cool, wet spells favor downy mildew.

Table 3: Example FRAC Rotation for the Northeast (Simplified)

| Step | FRAC Group | Example AI | Target Diseases | What This Means for Gardeners |

| Protectant | M02/M03 | Sulfur, Mancozeb | Black spot, powdery mildew | Start with broad coverage before infection. |

| Systemic | 3 (DMI) | Myclobutanil, Tebuconazole | Black spot, powdery mildew | Switch to a penetrant fungicide.Don’t repeat more than twice. |

| Alternative | 11 (QoI) | Azoxystrobin | Broad foliar fungi | Rotate to slow resistance. |

| Weather-triggered addition | 33 | Phosphites | Downy mildew | Add only in long, cool, wet spells when risk is high. |

| Reset | M02/M03 | Sulfur, Mancozeb | Broad protection | Return to protectant to restart rotation. |

Note: Weather-triggered additions are conditional sprays inserted only when environmental conditions favor downy mildew.

Conclusion

In the Northeast U.S., fungal diseases remain a primary challenge for rose growers. By integrating resistant cultivars, cultural practices, beneficial insects, and careful fungicide rotation, gardeners can maintain sustainable rose health. With these strategies, roses will continue to provide beauty, fragrance, and long-term landscape value.

Resources

American Rose Society. (2020). A guide to rose diseases and their management. Shreveport, LA: American Rose Society.

American Rose Trials for Sustainability. (n.d.). Results and regional trial locations. Retrieved August 2025, from https://www.americanrosetrialsforsustainability.org

Chute, M., & Chute, A. (2015). Roses for New England: A guide to sustainable rose gardening. Rhode Island Rose Society Press.

Daughtrey, M. L., & Benson, D. M. (2005). Principles of plant disease management in the landscape. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 43(1), 559–578. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.140828

Horst, R. K. (2015). Westcott’s plant disease handbook. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Horst, R. K., & Cloyd, R. A. (2013). Compendium of rose diseases and pests (2nd ed.). St. Paul, MN: APS Press.

Krasnow, C. (2025). Managing Botrytis on bedding plants. UConn Extension. https://doi.org/10.61899/ucext.v2.144.2025

Kukielski, P. (2015). Roses without chemicals. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Lentz, E. (2025). Developing an IPM plan for San Jose scale. UConn Extension. https://doi.org/10.61899/ucext.v2.111.2025

Ritchie, G. A. (2003). The rose doctor: A key for diagnosing problems in the rose garden. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Scanniello, S. (1996). A year of roses. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Scanniello, S., & Phillips, P. (1994). The rose garden. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Schumann, G. L., & D’Arcy, C. J. (2010). Essential plant pathology (2nd ed.). St. Paul, MN: APS Press.

Winne, P. (2021). Connecticut buyer’s guide to roses. Connecticut Horticultural Society Newsletter, April 2021, 4–5.

Zuzek, K., Richards, M., McNamara, S., & Platt, H. (1995). Roses for the North: Performance of shrub and old garden roses at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum (Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Report 237). University of Minnesota.

The information in this document is for educational purposes only. The recommendations contained are based on the best available knowledge at the time of publication. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. UConn Extension does not guarantee or warrant the standard of any product referenced or imply approval of the product to the exclusion of others which also may be available. The University of Connecticut, UConn Extension, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.